The investment firm Robert Nelsen co-founded in 1986, Arch Venture Partners, has racked up billions in profits from early stakes in companies developing methods to detect and treat cancer and other diseases.

In his personal life, Nelsen, 60 years old, downs a daily cocktail of almost a dozen different drugs, including rapamycin, metformin, taurine and nicotinamide mononucleotide, all of which he says help prevent illness and promote longevity. Nelsen has a full-body MRI every six months, sees a dermatologist every three months and has annual blood tests to detect cancer. At his home in the Rocky Mountains, he works out in an “electric suit” that he says emits low-frequency impulses to build muscle and improve health.

“I know I will get cancer, I just want to catch it early,” says Nelsen, who says an MRI several years ago has already identified thyroid cancer at an early stage. He has seen family members die of the disease.

“Bob has a big fear of death,” says his wife, Ellyn Hennecke.

Nelsen shows some of the medications he takes in his efforts to prevent illness and promote longevity. At right, the ‘electric suit’ that he uses for workouts.NATALIE BEHRING FOR THE WALL STREET JOURNAL

Nelsen’s latest and largest investment—several hundred million dollars, he says—is in a company attempting something even more ambitious than aiding health and longevity. Altos Labs, based in the San Francisco Bay Area, San Diego, and Cambridge, U.K., is working on ways to rejuvenate cells to eliminate disease—an approach called epigenetic reprogramming. Nelsen and Altos’s founders believe they can turn the clock back on aging cells to restore functions characteristic of younger cells.

Arch is the largest institutional investor in Altos, which already has $3 billion of committed investments, likely making it the biotech industry’s best-funded startup on record.

Nelsen is characteristically unrestrained when discussing Altos’s prospects.

“Epigenetic reprogramming is the biggest thing in healthcare in 100 years. Or ever,” he says. “We will clearly live much healthier and longer lives if this works.”

That’s a huge if. Cellular rejuvenation has yet to be proven effective as a treatment. So far, the only data Altos and others in the field have produced is in mice, suggesting they are a long way from rolling out any products. Skeptics doubt cells can be reprogrammed to ward off age-related illnesses.

Nelsen realizes Altos faces imposing obstacles.

“The big question is, will this work in humans,” Nelsen acknowledges. “At first blush, it seems too good to be true.”

Nelsen favors designer jeans and black T-shirts, looking more like an upscale bike messenger than a deep-pocketed investor. He doesn’t hold a medical degree and never worked in a lab.

A native of Walla Walla, Wa., Nelsen studied biology and economics at the University of Puget Sound before getting an M.B.A. at the University of Chicago. His approach to building Altos is the same as with past investments: Identify leading scientists with ambitious ideas and back them with huge checks and other support.

“Cool things happen when you put scientists together,” he says.

Then, Nelsen prods them to make progress.

Founders of companies Nelsen invests in say they’ve learned to appreciate his energy, enthusiasm and judgment, especially in difficult situations. PHOTO: NATALIE BEHRING FOR THE WALL STREET JOURNAL

“He sends a text almost every day—‘Chat?’ or ‘Need to talk,’ says Richard Klausner, a successful biotech entrepreneur who is Altos’s chief scientist and developed the idea behind the company with investor Yuri Milner. “Then I’ll call him, and he texts ‘Can’t talk.’”

Sometimes, Nelsen sends company founders more urgent messages, such as “DNFIU”—Do Not Fuck It Up. His manic energy can lead to confrontations. Nelsen drives his GMC Yukon so aggressively that some friends avoid riding with him. He’s started fights with supermarket customers who resisted using plastic bags.

“I hate plastic bag bans, because the assumption that they are better for the environment than paper is flawed and I am grown up enough to not have government choose my bag for me,” Nelsen says.

Founders of companies Nelsen invests in say he is easily distracted and spends a lot of time staring at his phone. But they’ve learned to appreciate his energy, enthusiasm and judgment, especially in difficult situations.

“Bob isn’t a scientist but he has fantastic intuition, makes decisions fast and is a terrific partner in a crisis, he always stays calm,” Klausner says.

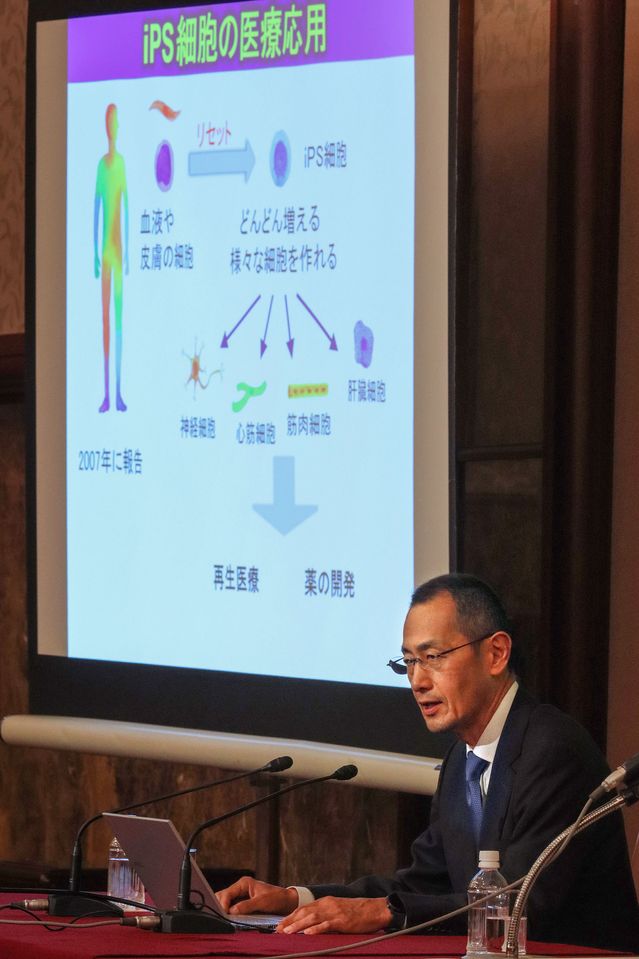

Taking cells back to their youthful, healthier state long captured the imagination of scientists, but seemed unlikely. Then a breakthrough paper published in 2006 by Japanese scientist Shinya Yamanaka and a colleague showed mature skin cells of mice could be reprogrammed into primordial, immature stem cells—called induced pluripotent stem cells—in effect resetting their molecular clocks. Yamanaka, who later shared a Nobel Prize for work in this area, is an adviser to Altos. In 2016, Spanish biochemist Juan Carlos Izpisua Belmonte, Altos’s founding scientist, showed how the age of cells could be reverted without changing their genome and identity. His work demonstrated the potential for toggling between the ‘old’ and ‘young’ states of cells—the basis for Altos’s effort to rejuvenate cells.

Nobel Prize winner Shinya Yamanaka, here in Tokyo in 2019, made a breakthrough in reprogramming cells. PHOTO: YOSHIO TSUNODA/ZUMA PRESS

“If we can turn the clock back so cells are healthy and resilient, you can reverse disease,” Klausner says.

But there’s limited evidence cellular rejuvenation can be done safely or that it can be an effective way to combat disease or reverse the effects of aging. Some scientists are downright dismissive of the idea. Dr. Richard A. Miller, a professor of pathology at the University of Michigan, who says he hasn’t followed Altos’s efforts, argues that it’s simplistic and misguided to explain illness as the result of cells getting older. In any aging body, cells divide, die, are replaced and change, he notes. So it’s unclear if reprogramming cells can ward off sickness, even if it could be done successfully and safely, he says.

“Aging is something that happens to bodies, not to cells,” Miller says. “The reprogramming idea seems to be a shortcut to try to make cells ‘younger’ in the hopes that this will somehow fix everything. There’s no evidence this will work.”

Others say the approach has both potential and enormous risk.

“Reprogramming technology is powerful, and it works in cells, but when you do it in animals it’s more of a challenge, so an actual product or therapy will be tough,” says Paul Knoepfler, a stem-cell researcher at the University of California, Davis. “You can get cells to be younger but if you get it just a little wrong you can create tumors. There’s not much room for error.”

While Yamanaka’s earlier work demonstrates that “cellular reprogramming can reverse the oldness or agedness of cells to take them back to a youthful cellular state in the form of iPS cells,” that work was done in cells in a Petri dish in a lab, Knoepfler says. “It’s much less clear,” he says, if Altos or others can safely reverse the aging of cells and tissues in a person.

Nelsen and Altos are raiding academic institutions and other organizations to hire nearly 500 scientists around the globe, including several Nobel Prize winners.

“It’s an all-star team of scientists,” Knoepfler says. “They have the freedom to pursue questions, the money makes a difference, they can take more risks…If anyone can do it, they can.”

Nelsen’s track record suggests Altos has a shot at success. His firm has backed successful biotechs including Juno Therapeutics, Illumina, Alnylam and Agios. Industry publication STAT recently named Arch the most successful biotech venture-capital firm of the past year.

Nelsen says he was convinced to bet on Altos by “the breadth of different animal models” demonstrating cell rejuvenation, the quality of the scientists joining the company and the goal of “reversing, not treating disease.”

“My goal is not to make a trillion-dollar company,” he says. “It’s to profoundly restructure a reactive broken industry into a curative industry that has profound impact on humans.”