@cremieuxrecueil

2h • 10 tweets • 4 min read • Read on X

Does the U.S. overpay for drugs?

Common knowledge says “Yes”.

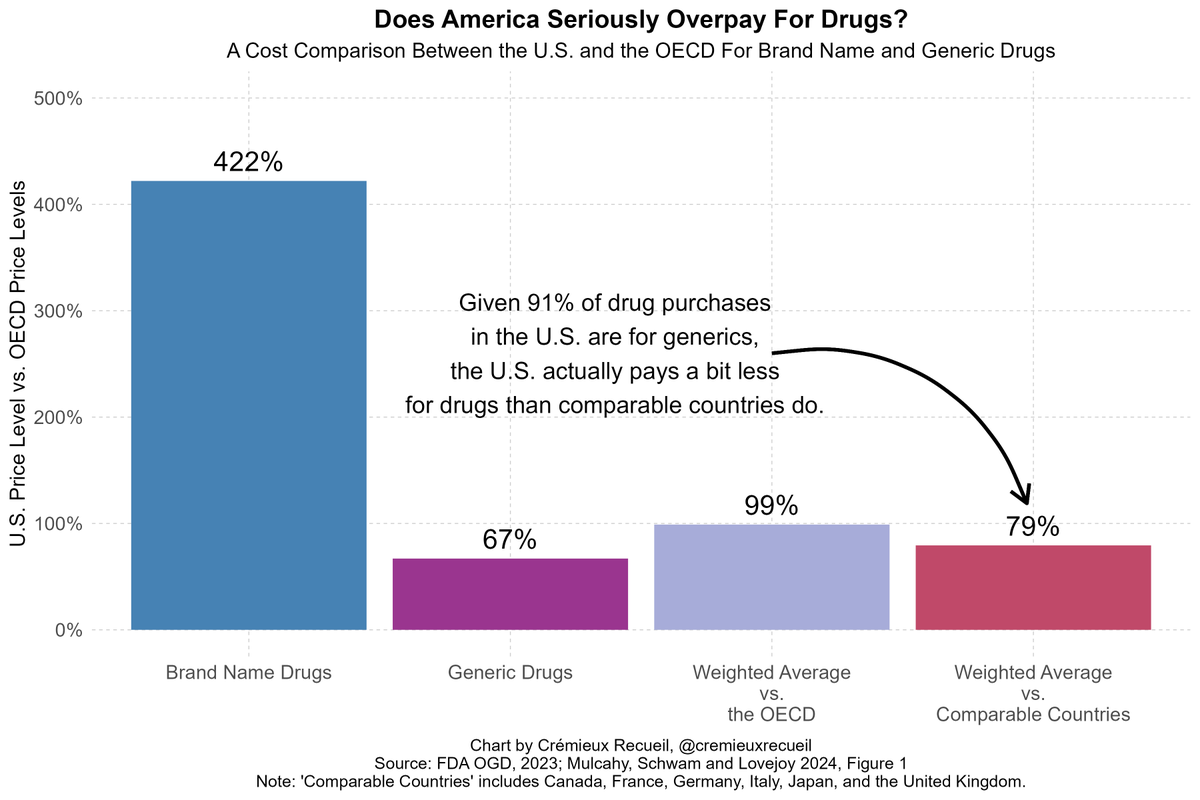

Real data says “No”, because the U.S. gets favorable prices for generic drugs and it primarily consumes generic drugs. In fact, they’re 91% of prescriptions

But then, we have a mystery:

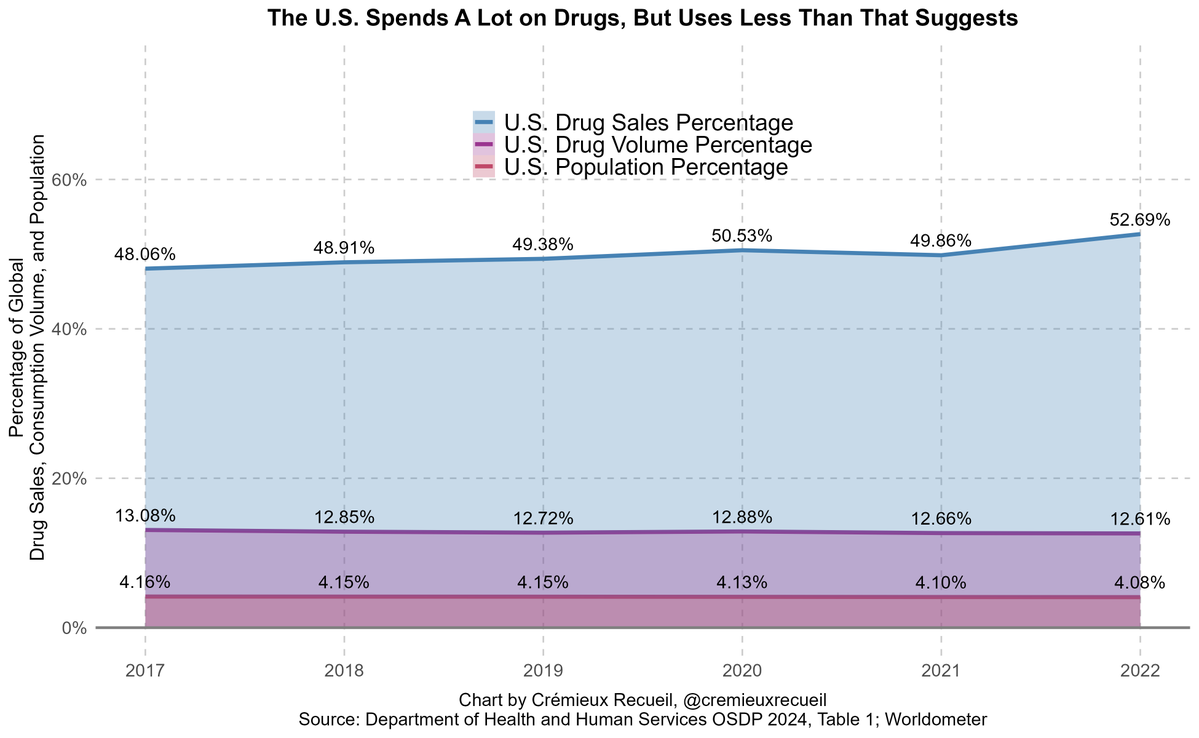

If the prices America tends to pay are, in fact, reasonable, then why does it account for such a large share of all global spending on drugs?

When we think of the U.S. overpaying, we’re thinking about 9% of purchases and forgetting the 91% for which it has better prices

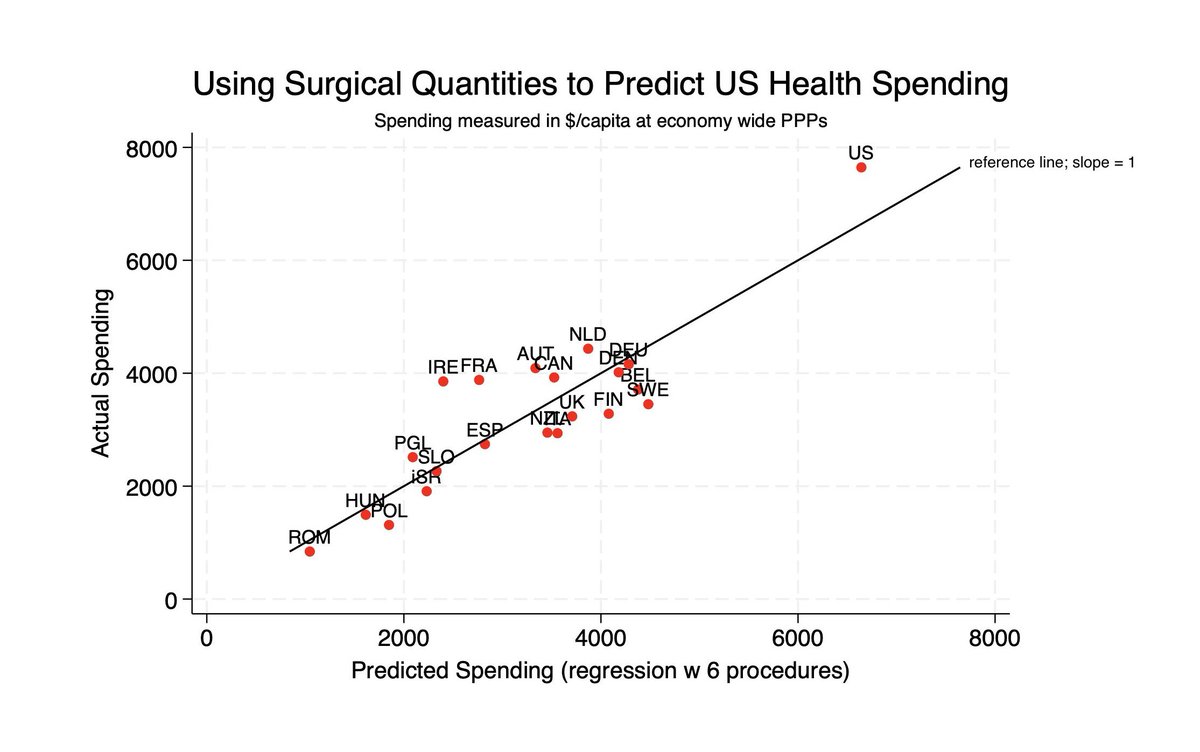

The reason the U.S. does so much health spend is not high prices, it’s high consumption

America is rich, so it buys a lot of healthcare! For example:

The U.S. also accounts for an outsized share of non-prescription purchases, for which the prices are also still fine.

If you want to get to the point where America matches poor countries, just stop right there, because they have lower prices, but also consumption, and quality.

And, what value does the U.S. get for that high consumption?

Well generally better health outcomes for things the health system actually controls.

But American health lags due to diseases of affluence and violence.

(Ed.: I do not know what the above chart is supposed to be telling me.)

Go figure.

America eats itself to death and attempts to eat its way out of eating itself to death, too. That’s being absurdly rich for you.

The question is, why bemoan this?

This is not to say there’s nothing the U.S. can do to lower drug prices and get down spending while maintaining its consumption volume.

There’s a massive amount of deregulation that can be done to cut non-generic drug prices and much else, it’s just harder than price controls.

Sources:

fda.gov/media/165435/d…

pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11…

aspe.hhs.gov/sites/default/…

cremieux.xyz/p/grading-the-…

Thread on MFN policy in health:

@Jabaluck

2h • 11 tweets • 3 min read • Read on X

Good news everyone! The unpopular and seemingly irrelevant lecture I give in my health econ class on “Most favored nations agreements” just became prophetically relevant.

Bad news everyone! This is a terrible policy.

There are two separate questions:

- Will MFNs lower prices?

- Is lowering drug prices a good idea?

On point 1), the answer is: probably not. My colleague Fiona Scott Morton has a paper on what happened when Medicaid introduced MFNs. MFNs essentially say Medicaid has to pay a lower price than all other insurers for drugs.

There are two ways insurers can comply. They could charge Medicaid less. Or they could charge other insurers more. What happened?

Prices didn’t change much for drugs under patent with no generic competition (~ same price everywhere) or generic drugs (~ same price everywhere), but prices rose by 4% for drugs facing generic competition (different prices prior to the MFN, now uniform)

https://www.jstor.org/stable/2555805?seq=1

Dubois, Gandi and Vasserman simulate something very close to the policy Trump is proposing. Pharma companies don’t want to cut prices in the US to the level of prices in Sierra Leone. Instead, they raise prices in Sierra Leone. shoshanavasserman.com/files/2022/DGV…

So, prices will probably increase in low-income countries and people in the US won’t save 50-80% as you might naively project if you didn’t understand that prices are determined in equilibrium.

Would it be good if prices fell in the US? This is a more complicated question which I engage with here:

tldr; we don’t want to lower prices on average, but some drugs are too expensive.

If it’s better for prices to be higher, does this mean this policy is good?

No, because the policy will still lower pharma revenue in total (it forces them to price above the profit maximizing level in other countries), meaning they also have diminished incentives to innovate!

In other words, this is a bad policy that would only be pursued by people who hadn’t thought through the consequences that probably harms everyone for no reason.

*(I misspelled the cite, it’s: Dubois, Gandhi and Vasserman)

• • •

Elasticities of healthcare innovation to spending:

Grok’s .02:

Let’s evaluate the assertions in the X thread by Crémieux (@cremieuxrecueil) posted on May 12, 2025, and address your question about whether the 90% generics figure refers to dollar volume or unit volume, as well as the implications for the executive order on drug prices issued on May 11, 2025. I’ll break this down systematically, assessing each claim in the thread, clarifying the generics percentage, and analyzing the executive order’s potential impact.

Overview of the Thread

The thread challenges the notion that the U.S. overpays for pharmaceuticals, asserting that while brand-name drugs are significantly more expensive in the U.S., generics (which dominate U.S. consumption) are cheaper, leading to a lower overall weighted average price compared to other OECD countries. It also explores why the U.S. spends so much on drugs despite reasonable prices, attributing this to high consumption rather than high prices. The thread concludes with suggestions for lowering costs through deregulation rather than price controls.

Evaluation of Assertions in the Thread

1. Claim: The U.S. does not overpay for drugs because 91% of prescriptions are generics, and generics are cheaper in the U.S. than in comparable OECD countries.

-

Supporting Evidence in Thread: The chart shows U.S. brand-name drugs at 422% of OECD price levels, generics at 67%, with a weighted average of 99% (vs. OECD) and 79% (vs. comparable countries: Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, UK). The 91% generic prescription share is cited.

-

Evaluation:

-

Accuracy of Generic Share: The 91% figure for generic prescriptions aligns with data from the web results. Statista reports that 91–92% of U.S. prescriptions dispensed from 2020–2023 were for generics, consistent with historical trends (e.g., 90% in 2019 per the Association for Accessible Medicines). This claim is accurate.

-

Price Comparison: The chart’s data, sourced from the FDA’s Office of Generic Drugs (OGD, 2023) and Mulcahy, Schwam, and Lovejoy (2024), is credible. It shows generics at 67% of OECD levels, meaning U.S. generic prices are indeed lower. This is supported by the FDA’s Generic Competition and Drug Prices report, which notes that increased generic competition (often involving Indian manufacturers, who supply 40–47% of U.S. generics) drives prices down significantly—sometimes to 10–20% of brand prices after multiple generic entrants. This claim is accurate.

-

Weighted Average: The weighted average (99% vs. OECD, 79% vs. comparable countries) depends on the 91% generic prescription share. Since generics are cheaper, they pull the average down despite high brand-name prices. This methodology is standard in pharmacoeconomic studies, though it assumes uniform consumption patterns across countries, which may oversimplify (e.g., the U.S. may use more expensive generics within that 91%). This claim is mostly accurate but could be nuanced by consumption patterns.

-

Caveat: The chart focuses on price levels, not total spending, which the thread addresses later. It also doesn’t account for rebates or discounts (common for brand-name drugs in the U.S.), which could lower effective prices but aren’t reflected here.

2. Claim: The U.S. accounts for a large share of global drug spending (48.9% in 2022) despite only 4.1% of the population, not because of high prices but due to high consumption.

-

Supporting Evidence in Thread: A chart shows U.S. drug sales at 48.9% of global sales (vs. 4.1% population share) from 2018–2022. Another chart plots U.S. health spending against predicted spending based on GDP per capita, showing the U.S. spends more than expected. The thread attributes this to high consumption, not prices, and cites higher U.S. consumption of healthcare services.

-

Evaluation:

-

Spending Share: The 48.9% figure for 2022 aligns with industry reports (e.g., IQVIA Institute, 2023, reports U.S. share at 43–50% of global pharmaceutical spending in recent years). The population share (4.1%) is accurate (U.S. population ~340 million / global ~8 billion). This claim is accurate.

-

High Consumption: The thread’s assertion that high consumption drives spending is supported by data. The U.S. spends $4.9 trillion on healthcare annually (2024), or ~$14,500 per capita, far exceeding OECD averages (~$4,900 per capita, per OECD 2024). The U.S. also has higher utilization rates for prescription drugs (e.g., 12.8 prescriptions per person annually vs. OECD average of 9.5, per Commonwealth Fund, 2023). The thread’s chart showing health outcomes (better for treatable conditions, worse for lifestyle diseases) supports the idea that the U.S. consumes more healthcare to address “diseases of affluence” (e.g., obesity, diabetes). This claim is accurate.

-

Spending vs. GDP: The chart showing U.S. health spending above predicted levels based on GDP per capita is consistent with economic analyses (e.g., CMS National Health Expenditure Data, 2024). The U.S. spends 17.3% of GDP on healthcare vs. an OECD average of 9.3%. This supports the thread’s argument that wealth-driven consumption, not just prices, drives spending. This claim is accurate.

-

Caveat: While consumption is a major factor, high brand-name drug prices (422% of OECD levels) still contribute significantly to spending, especially for the 9% of prescriptions that are branded but account for a disproportionate share of costs (see below).

3. Claim: The U.S. gets better health outcomes for conditions the health system controls, but lags due to diseases of affluence and violence.

-

Supporting Evidence in Thread: A chart compares U.S. health outcomes to other countries, showing better outcomes for treatable conditions (e.g., cancer survival rates) but worse for lifestyle diseases (e.g., obesity-related conditions) and violence.

-

Evaluation:

-

Treatable Conditions: The U.S. excels in outcomes for conditions like cancer, with a 5-year survival rate for breast cancer at 90.2% (vs. OECD average of 87.4%, per OECD 2024) and lung cancer at 23.7% (vs. 20.6%). This is partly due to high spending on innovative drugs like Keytruda (Merck’s top seller, $29.5 billion in 2024) and access to advanced treatments. This claim is accurate.

-

Diseases of Affluence and Violence: The U.S. has higher rates of obesity (42.4% of adults, CDC 2024, vs. OECD average of 23%) and related conditions like diabetes (10.5% prevalence vs. 7.3% OECD). Homicide rates are also higher (7.8 per 100,000 in 2023, FBI, vs. OECD average of 2.6). These factors drag down overall health metrics like life expectancy (78.5 years vs. OECD average of 80.3). This claim is accurate.

-

Caveat: The thread oversimplifies by not addressing systemic issues like healthcare access disparities (e.g., 8.5% uninsured in the U.S., per Census 2024) or social determinants of health, which also impact outcomes.

4. Claim: Lowering drug prices can be achieved through deregulation, not price controls.

-

Supporting Evidence in Thread: The thread suggests deregulation to cut non-generic drug prices, linking to a thread on Most Favored Nation (MFN) policies (Thread 1) and elasticities of innovation (Thread 2).

-

Evaluation:

-

Deregulation Potential: Deregulation, such as streamlining FDA approvals for generics or reducing patent barriers, can lower prices by increasing competition. The FDA notes that generic entry reduces prices by 50–80% with 2–3 competitors. Examples include accelerating biosimilar approvals (e.g., for biologics like Humira, which dropped from $20 billion/year after generics entered in 2023). This claim is plausible.

-

Price Controls Critique: The linked MFN thread (Thread 1) argues that MFN policies (tying U.S. prices to lower international prices) may raise global prices (e.g., in low-income countries) and reduce innovation by lowering pharma revenue. Studies like Dubois, Gandhi, and Vasserman (2025) support this, showing price increases in other countries (e.g., 4% for drugs facing generic competition under Medicaid MFN). This critique is valid.

-

Caveat: Deregulation carries risks, such as reduced safety oversight (e.g., 31 FDA warning letters to Indian manufacturers for data integrity issues, 2015–2017). The thread doesn’t address how to balance innovation with cost reduction, a key concern in Thread 4.

Clarifying the 90% Generics Figure: Dollar Volume or Unit Volume?

The thread states that 91% of U.S. drug purchases (prescriptions) are generics. Your question is whether this 91% refers to unit volume (number of prescriptions) or dollar volume (spending), as this distinction impacts the executive order’s effect.

-

Unit Volume (Prescriptions): The 91% figure refers to the share of prescriptions dispensed, not spending. Web results from Statista confirm that 91–92% of U.S. prescriptions dispensed from 2020–2023 were generics, aligning with the thread’s claim. This is a standard metric in pharmaceutical studies, focusing on volume (number of prescriptions filled).

-

Dollar Volume (Spending): Generics account for a much smaller share of spending due to their lower cost. Statista data shows that in 2022, generics (including branded and unbranded) accounted for ~15.5% of total U.S. medicine spending ($638 billion), with branded generics at 7% and unbranded generics at 8.5%. Brand-name drugs, despite being only 9% of prescriptions, made up ~84.5% of spending. This disparity arises because brand-name drugs like Keytruda ($29.5 billion in 2024) are far more expensive than generics (e.g., levothyroxine, a top generic, costs ~$0.10–$0.30 per pill).

Conclusion: The 91% generics figure in the thread refers to unit volume (prescriptions), not dollar volume. By spending, generics are ~15–16% of the total, while brand-name drugs dominate at ~84–85%.

Impact of the Executive Order on Drug Prices (May 11, 2025)

The executive order, as described in the web results (“Lowering Drug Prices by Once Again Putting Americans First,” White House, April 15, 2025), aims to:

- Encourage generic and biosimilar development to increase competition.

- Improve transparency in the Medicare Drug Price Negotiation Program, prioritizing high-cost drugs.

- Minimize negative impacts on innovation.

- Promote a competitive, efficient pharmaceutical value chain to lower prices.

- Address anti-competitive behavior by manufacturers (e.g., via DOJ, Commerce, FTC).

Analysis of Impact:

-

Focus on Generics: The thread suggests that since 91% of prescriptions are generics (by volume) and U.S. generic prices are already low (67% of OECD levels), the executive order’s impact may be minimal for most prescriptions. This is partially true:

- Generics are already competitive, with prices dropping significantly after patent expiry (e.g., FDA data shows prices fall 50–80% with 2–3 generic competitors). The executive order’s push for more generics and biosimilars may further lower prices, but the effect will be marginal since generics are already 33% cheaper than OECD averages.

- By unit volume, 91% of prescriptions are generics, so the order’s impact on the majority of prescriptions may indeed be small.

-

Brand-Name Drugs (High-Priced Non-Generics): Your intuition is correct that the executive order will have a larger impact on high-priced brand-name drugs (the 9% of prescriptions by volume but 84–85% by spending):

- Brand-name drugs are 422% of OECD price levels, and high-cost drugs are the focus of Medicare price negotiations (e.g., drugs like Keytruda, which cost $150,000–$200,000 per patient annually). The executive order’s emphasis on negotiating prices for high-cost Medicare drugs directly targets these brand-name drugs.

- Transparency in negotiations and anti-competitive measures (e.g., addressing “pay-for-delay” deals) could lower brand-name prices significantly. For example, Medicare negotiations under the Inflation Reduction Act (2022) have already reduced prices for drugs like Eliquis by 56% (CMS, 2024).

-

Overall Spending Impact: Since brand-name drugs dominate spending (84–85%), even a small reduction in their prices could have a substantial effect on total U.S. drug expenditure. For example:

- If brand-name drug prices (84.5% of $638 billion = $539 billion in 2022) were reduced by 10%, that’s a $53.9 billion savings, overshadowing any savings from generics (15.5% of $638 billion = $99 billion, where a 10% reduction saves $9.9 billion).

- Thus, the executive order’s impact will not be “minimal” on total spending—it will be significant due to its focus on high-priced non-generics.

-

Innovation Concerns: Thread 4 (Jason Abaluck) and Thread 1 (MFN policy) highlight risks to innovation if prices are lowered indiscriminately. The executive order’s clause to “minimize negative impacts on innovation” suggests a balanced approach, but reducing brand-name prices could still reduce R&D investment (e.g., Thread 2’s elasticity data shows a 100% demand increase yields 154% more drugs, implying price reductions may cut innovation).

Specific Implications:

-

Generics (91% by Volume, 15–16% by Spending): The executive order may slightly lower generic prices via increased competition, but the impact will be limited since prices are already low. For example, further generic entry might reduce prices by an additional 5–10%, saving $5–10 billion annually on the $99 billion generic market.

-

Brand-Name Drugs (9% by Volume, 84–85% by Spending): The order’s focus on Medicare negotiations and anti-competitive practices will likely lower brand-name prices significantly. A 20% reduction in brand-name prices (a realistic target based on IRA outcomes) would save $107.8 billion annually on the $539 billion brand-name market.

-

Total Impact: The executive order’s effect will be substantial on overall spending due to brand-name drugs, contrary to the thread’s implication of minimal impact. However, for the average consumer filling prescriptions (91% generics), the price difference may be less noticeable.

Summary of Evaluation

-

Thread Assertions:

- The claim that the U.S. doesn’t overpay due to low generic prices (91% of prescriptions) is mostly accurate but oversimplifies by focusing on price levels, not spending. The weighted average price is indeed lower, but total spending is high due to consumption.

- High U.S. spending due to consumption, not prices, is accurate, supported by data on utilization and GDP-adjusted spending.

- Better outcomes for treatable conditions but worse for lifestyle diseases is accurate, though systemic issues are underexplored.

- Deregulation as an alternative to price controls is plausible but lacks detail on implementation and risks.

-

90% Generics Figure: It refers to unit volume (prescriptions), not dollar volume. Generics are 91–92% of prescriptions but only 15–16% of spending; brand-name drugs dominate spending at 84–85%.

-

Executive Order Impact: The order will not have a minimal effect—it will significantly impact total spending by targeting high-priced brand-name drugs (84–85% of spending), despite generics being 91% of prescriptions. Savings from brand-name price reductions (e.g., $50–100 billion annually) will far outweigh savings from generics.

Additional Notes

-

MFN Policy Concerns: Thread 1’s critique of MFN policies (raising global prices, reducing innovation) aligns with the executive order’s cautious approach to innovation. However, the order’s focus on competition and negotiation may mitigate some of these risks.

-

Consumption Patterns: The thread’s focus on consumption explains why spending remains high despite lower weighted prices, but it doesn’t address affordability issues for patients facing high out-of-pocket costs for brand-name drugs.

-

Data Limitations: The thread’s data is from 2023/2024, predating the executive order. Future price changes under the order may alter the weighted average, especially if brand-name prices drop significantly.

If you’d like a deeper analysis of the executive order’s provisions, specific drug price impacts, or further data on generics vs. brand-name spending, let me know!