This could also mean that as men get older and develop more plaque, lower LDL-C targets are required to prevent events further down the line.

2 Likes

This OR being high in men is a reflection of women simply being 10 years behind men in vascular disease. If you adjust for that - compare a 50 year old man to 60 year old woman - the numbers will track pretty nicely.

We see menopause as time where visceral adiposity changes, metabolic syndrome and vascular disease progression in women start looking similar to the trajectory of men.

I’d not interpret this as needing to escalate therapy based on age, instead, if tightly managing one’s ApoB, Insulin sensitivity, and Blood Pressure … one shouldn’t form new disease - but as a backup, yes, get intermittent screening. For example a CT calcium and Carotid Intimal Thickness U.S. or just grab a whole body MRI like we did at SimonOne such that we had an MRA neck and brain - so know that our vessels (both large and small) are free of disease.

Dr. Dayspring properly points out, that once you have disease, progression is unpredictable. So the goal is to manage in a state of no disease, and if you have disease, manage your ApoB and other targets more tightly to stabilize and encourage disease regression.

We are in a time, where with moderate resources, many people are able to afford these tests, and serially monitor.

4 Likes

adssx

#871

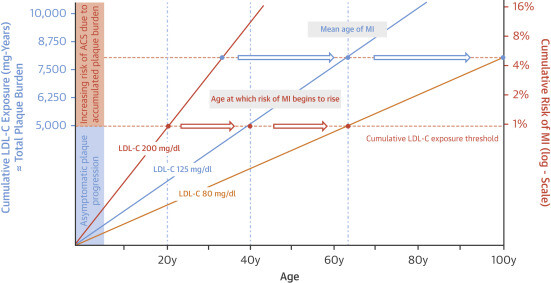

You make a good point. These adjusted OR are compatible with a risk of coronary atherosclerosis based on cumulative exposure. I did this chart in ChatGPT so that f(apoB+10, age) ~ 1.2 f(apoB, age) and f(apoB, age+5) ~ 1.4 f(apoB, age):

In this model (and consistent with Faridi et al. 2024), the cumulated apoB burden cannot be reversed over time, so very intensive apoB lowering is needed to compensate for aging, suggesting that we have to maintain apoB extremely low over your lifetime. Hopefully, there’s a threshold of cumulative exposure under which your risk is nil:

And hopefully as well, you can somehow reverse your risk to avoid going above that threshold.

All of that is speculative, but it “makes sense” to me and suggests that “lower for longer is better”. I don’t know what kind of research could confirm or infirm the above.

4 Likes

adssx

#872

They adjusted for “serum lipoprotein value, age, sex, race/ethnicity, family history of premature ASCVD, BMI, HbA1c, systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, HDL-C, triglycerides, and Lp(a) ≥125 nmol/L” so the male risk seems independent from age.

And even if you take into account that before menopause the apoB of men is about 20 mg/dL higher than women at the same age, this gives you an increased risk of 1.20^2 = 1.44. Far from 3.70. Similarly, even if you assume “women simply being 10 years behind men in vascular disease” then that’s 1.44^2 = 2.1, still way below 3.70.

So, women seem to have some anti-atherogenic power… (Endogenous oestrogens?)

2 Likes

Either estrogen is cardioprotective or androgens (more specifically DHT) are a risk factor.

May need to move it 15 years … but the number one killer and disabler of women is vascular disease … it’s just delayed. Yes, the thought is estrogen. The challenge there, is exogenous replacement doesn’t seem to completely fix this issue. We however have better data from oral formulations on this issue and they complicate matters by being non-bioidentical (except estradiol) and also inducing clotting factors when taken orally (which is why I only Rx estradiol topically).

4 Likes

adssx

#875

We need the OR for gender by menopausal status. If post menopausal women have the same OR as men (adjusted for age, BP, HbA1c, etc.) then it means that it’s mostly estrogens being protective and that the protection “disappears” post menopause.

4 Likes

So in this study the main criteria is Non HDL levels (Total cholesterol minus HDL). Essentially ignoring Triglyceride levels if I am seeing this correctly? The conjecture of some people (like Dr. David Diamond in the video from @Bicep above) is that low Triglycerides are a “marker” for the more benign LDL particle size and hence not as indicative of heart disease in a healthy individual. Does his assumption have any merit?

I am curious also why low triglyceride levels would not be included in the Faridi et al. study as a marker of good health along with the other factors they consider such as non-diabetic, decent blood pressure etc. It seems so easy to do as most people get that measure in their lipid blood panel and could have been included in the study.

3 Likes

mccoy

#877

I started to read the literature cited in the Faridi et al. article, with a cascade of citations. Basically, the reduction in the risk of major vascular events for every 40 mg/dL decrease LDL-C would be 20%.

This was true for higher (130) and lower (63 to 70) values of LDL-C.

Decreasing LDL-C by 40 mg/dL is obviously much harder for those who start with low values. The intervention would probably result in only a 10% risk reduction with ordinary means (low-dose statin).

The good news is that no statistical increase of adverse events was observed.

I find I’m not too encouraged by these values.

1 Like

Davin8r

#878

What about further lowering risk by other means, such as increasing VO2max and bringing blood pressure into optimal range? They should be additive to risk reduction from lowering LDL.

2 Likes

A_User

#879

The X post I linked above did include TG<100, if you aren’t satisifed with TG<150, and there are other studies using that criteria but not others showing that LDL still is harmful.

We’ll see the goal posts continue to be moved, first it was LDL doesn’t do anything, then it was LDL doesn’t do anything for the metabolically healthy, then they will further refine the criteria to some very strict definition of healthy, eventually they will ask the analysis to only be done in low carbers.

2 Likes

adssx

#880

What do you call “low values”? My ApoB went from ~100 mg/dL to ~60 mg/dL just with ezetimibe 10 mg. You can very easily lower by 40 mg/dL even if you’re at or below 100 mg/dL (rosuvastatin, ezetimibe, bempedoic acid, PCSK9i, diet, exercise, etc.).

You mention 20% above, so why do you say 10% here?

What do you mean? Which values?

3 Likes

Neo

#881

I know it’s “out of sample”, but any chance you could add LDL of 40 and 20 mg/dl and pull out the ages to 120 years here:

1 Like

ng0rge

#882

Just curious (and leaving aside that I said ACM and these charts show the presence of any plaque) but…isn’t that what this says?

Or does it mean that the group is too small to be “statistically significant”?

zazim

#883

Maybe you should have read what I actually posted. I said the vast majority of people do not have side effects. Somehow, you decided to come up with the nonsensical interpretation that the “vast majority” means no one has any side effects. My goodness.

mccoy

#884

I was disappointed, I imagined that the risk reduction in the model would have been greater; probably it was just my ignorance. Too much listening to Peter Attia, he makes it sound like a 100% risk reduction. The published numbers are moderate in the extent of risk reduction.

If starting at a low level let’s say 70 mg/dL, I set a 20 mg/dL as a reasonable decrease and that would constitute a 10% risk reduction. Starting from higher levels of course, we can reap the full benefits of a 0.2 risk reduction per 40 mg/dL decrease. And your -40 with a mere 10 mg Zetia is pretty good, we should wait and see the individual response.

Again, disappointment. My previous ignorance made me believe that the decrease in CV risk related to a significant drop in LDL like -40 mg/dL would have been more beneficial.

And yes, that’s the rationale that should be pursued, a single intervention alone is not enough to achieve substantial levels of risk reduction.

1 Like

adssx

#885

@Neo: I’ll try.

It means this indeed. Look at the chart.

@zazim: you posted “when they do studies comparing statins to a placebo, both groups have similar side effects”. This is the nonsense I refuted.

@mccoy: yes even though “lower is better” it’s unclear how much benefit you have going beyond LDL < 100 mg/dL, non-HDL < 130 mg/dL, and apoB < 80 mg/dL. You say that dividing these targets by ~2 brings a 20% risk reduction in MACE (and CVD? ACM?). If that’s true, it’s still a great intervention. Also: this doesn’t take into account the past LDL burden. What we want to know is: “If you stay below apoB of x mg/dL all your life, what’s your yearly risk of MACE vs someone at x+40?” If the theory of “cumulative LDL exposure” is correct then indeed what you can do with intensive LDL lowering is fairly limited once it’s “too late” and you want to start it as much as possible to stay below whatever threshold (ApoB of 40? 60? 80 mg/dL?).

2 Likes

mccoy

#886

The Sabatine et al., 2018 article takes MACE as a risk parameter. And, as you say, the sad truth is that, if cumulative exposure governs, an efficacious intervention should start early; the efficacy would be progressively lower as age increases.

So in my case, LDL-C in the range of about 70-90 mg/dL for decades, no metabolic risk factors, age 64, would you still consider a pharmaceutical intervention?

I’m aware that the intervention would probably start to carry its full effect at age 94. With a somewhat lesser effect at 74. So this would be a very long-term strategy. Which is not per se a bad thing.

There are other studies showing plaque regression at a certain threshold. I’m assuming that is the point where risk drops towards zero over time.

A_User

#888

What would you give if someone would say they can prevent you from having heart disease? Sure, you might worry about an increase in PD risk, or risk of Alzheimer’s disease. But the trade off is total prevention of the primary cause of death. One is off the table, the other ones might have a small increase. Less things to worry about and optimize for, not to mention lethal and non-lethal strokes decreasing.

(It might be something like statins + ezetimibe + PCSK9 inhibitor right now). Somewhat rough tools in the toolbox, but better than nothing and the gods of the future might be smiling back at us.

Yes it will be like using duct tape on a car, but would total prevention today be any different? Why do we think so?

(Total prevention is like beginning at maybe exactly 20 yrs old, but close enough, better than nothing).