A_User

#1438

Context matters, if you asked him that you wanted to try to avoid atherosclerotic disease forever he would probably say to target 30 mg/dl or lower.

There are barely any side effects of ezetimibe and PCSK9 inhibitor.

That must mean these are true longevity drugs. And obicetrapib might join that camp soon as well.

3 Likes

All exercise is not the same. If 4-5 days of exercise per week is optimal, what does that mean? Does he quantify the hours per day or type(s) of exercise one should do? Cardio, lifting, walking, Tai Chi, what?

RapMet

#1441

Well, there wasn’t that long ago we discussed various exercise studies which found that even light exercise provides 95% of the benefits of intense exercise. so, don’t know what to make of it. I guess these studies tend to change based on weather outside lol.

2 Likes

What I think is clear is that there is perhaps a minimum of 7,000 steps a day that provides useful exercise after that point there remain marginal improvements until people go into the endurance type of exercise.

5 Likes

adssx

#1443

By the same author: Omega-3 fatty acids in primary and secondary prevention of cardiovascular diseases 2024

The optimal levels of Ω-3 index appear to be 8% or greater,36 which has generally been accepted as the standard target for this risk factor. Furthermore, based on data evaluated in 2023 of a meta-analysis including 58 studies, practical recommendations to improve Ω-3 index to ≥8% are consumption of 1000–1500 mg/d EPA/DHA for at least 12 weeks. The inconsistent results of prior Ω-3 studies were likely heavily influenced by the complexity of Ω-3 bioavailability and dosing issues, but also may be related to the specific CVD outcome being studied. As discussed previously, there is data suggesting a more linear relationship between dosing and benefit with nonfatal CHD events and a plateau effect when analyzing dosing benefits involving CVD mortality.

One important question is whether EPA, DHA, or some combination of both is more effective in preventing CVD outcomes. There is the belief that EPA is better for CVD prevention given observations that DHA supplementation can increase LDL-cholesterol levels. One study found high-dose DHA increases LDL turnover and contributes to larger LDL particles compared with EPA; however, large LDL particles are linked to lower risk of CVD as compared to small LDL particles.

Regardless, there is a more significant amount of data involving the benefits of Ω-3 PUFAs and atherosclerotic plaque stability with EPA versus EPA + DHA.

Furthermore, a meta-analysis conducted by Jia et al., which included data from over 83,000 patients, found a 51% increased risk of AF with higher doses of Ω-3 (>1 g daily) and a much smaller increased risk (12%) associated with lower doses (≤ 1 g daily). In light of these findings, it may be advisable to consider shared decision-making regarding AF risk for individuals at high risk. However, for most patients, the cumulative cardiovascular benefits of low-dose Ω-3 likely outweigh the associated risks.

Conclusions: A robust and significant proportion of data supports the efficacy of Ω-3 at therapeutic levels in both the primary and secondary prevention of CVD. It appears the primary unanswered questions relate to the optimal mix of EPA and DHA and ideal target doses of these Ω-3 fatty acids. Research employing higher doses of Ω-3 typically results in more uniform CVD benefits, though these outcomes may vary according to the specific CVD endpoints assessed. The Ω-3 index has been proposed as a tool to navigate these dosage concerns, yet it has not gained widespread traction in clinical settings. It is evident an information gap exists on this topic, and RCTs utilizing the Ω-3 index could provide clarity. The AHA recommendations seem to align with current evidence, endorsing Ω-3 supplementation for individuals at elevated risk or established CVD and for those with elevated TG levels. Despite advancements in CVD treatment modalities, the medical community should consider the use of Ω-3 supplementation, especially when accounting for the solid empirical support it has demonstrated, rather than rejecting it based on neutral results from suboptimal trials that do not fully account for its complex bioavailability.

My conclusion based on the available evidence (and what I started last month):

- Measure omega 3 index

- If close to 8%: focus on diet

- If far below 8%, see how much you need to supplement: Omega-3 Index Calculator | OmegaQuant

- Supplement in EPA only accordingly. If at risk of AF, then limit the dose to 1 g/day.

- Remeasure 4 months later and adjust if needed.

5 Likes

A_User

#1444

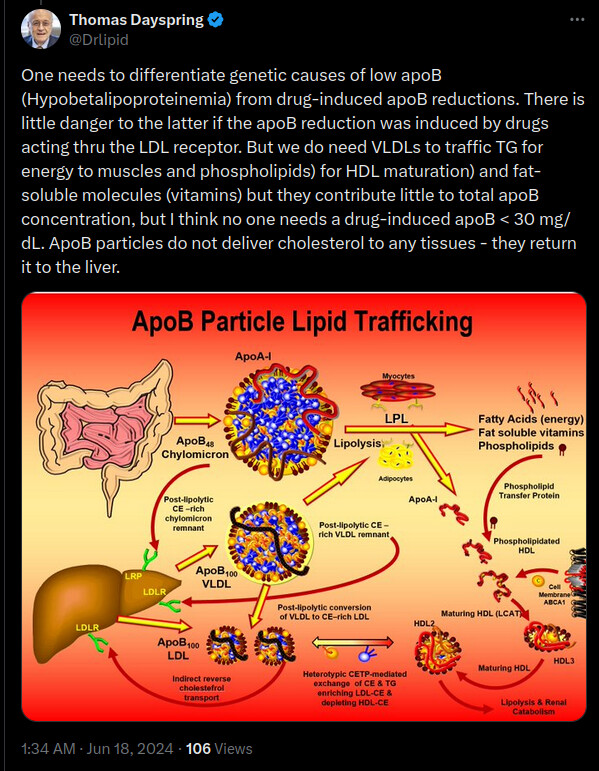

The boss has a more recent post of this:

I think he’s correct that there would be not much of any side effects.

Genetic causes might for example have an altered APOB gene causing malformed and malfunctioning apoB48 and apoB100, where the former is transporting lipids from the intestines. So if I would guess it kind of implies a level of precisely 0 apoB since it does not function, including apoB48. It would be interesting to look more in detail at PCKS9, NPC1L1, or CETP loss of function instead and related to fatty liver disease and fat soluble vitamins.

If you knock out PCKS9 you’re increasing LDL receptors on the liver making it take up more apoB’s, instead of affecting synthesis and transport of apoB48 from the intestines, for example. ApoB48 has a chance to deliver the energy and phospholipids to the muscles before the LDL receptors take them in at <30 mg/dl apoB. But he seems happy about 30 mg/dl apoB without any of these side effects.

It also probably depends on diet and other lifestyle factors if so. If it’s high in saturated fat that might cause fatty liver more (increase in serum LDL from it might be downregulation of LDL receptors to protect the liver).

So I’m targeting 30 mg/dl apoB to halt or prevent the progression of atherosclerosis and all of the negative events (stroke, heart attack, exercise intolerance, heart pain, etc), maybe even lower later. If there was any reason to believe it would increase fatty liver or vitamin deficiencies at lower levels, that I assume can be easily monitored.

5 Likes

It seems my statin intolerance was worse than I expected. Even 5 mg of Atorvastatin daily caused muscle spasms in my calves and weakness in my thigh muscles. I have switched to 5 mg of Atorvastatin Mon-Wed-Fri. This is much better, and the spasms are gone along with most of the weakness. I guess only time will tell whether this schedule causes problems.

My LDL and ApoB without the statin is 68.

My LDL and ApoB with a daily 5 mg statin is 48.

So, maybe I can hit 55-60 with this new dosing regime? Thoughts?

3 Likes

RapMet

#1448

Never measured ApoB. Does it always equal LDL?

1 Like

My LDL and ApoB are the same at these low levels. When my LDL was higher (120) my ApoB was a bit lower (108).

1 Like

mccoy

#1450

NO, there is a thread about it (let’s see if I can find it), it hoovers usually in the range of LDL plus or minus 10 mg/dL, but there is no general rule.

Anyway, non-HDL is seemingly the best proxy for ApoB

3 Likes

adssx

#1451

And if you don’t have access to apoB you can calculate eLDL-TG by yourself and eLDL-TG is apparently even better than apoB, LDL-C and non-HDL-C:

2 Likes

A_User

#1452

I find it unlikely it’s better than apoB because of an association study, also a marker that might be partly elevated by obesity or insulin resistance is of no use to me who don’t have that. There’s confounding.

adssx

#1453

I haven’t checked the rest of the literature, but I still think that with LDL-C, non-HDL-C, and the ability to calculate eLDL-TG, people don’t absolutely need apoB if it’s not included by default in their usual package. Of course, if they can have it, they should go for it.

2 Likes

A_User

#1454

I don’t think so, because it’s most likely a worse marker. Your eLDL-TG can be okay but your apoB terrible, and then you’re getting ASCVD since the latter is causal and the former just association with confounding.

It might simply be testing for obesity and insulin resistance, for example. Just because you’re not that because they increase risk doesn’t mean you’re fine. This is a common trick people use to justify suboptimal apoB, as well, even though it’s their own health.

adssx

#1455

Do you have a source? Dr Lipid claims that it’s been known for 20 years that LDL-TG is better than LDL-C. I haven’t checked the literature.

I can’t think of a situation where LDL-C AND non-HDL-C AND eLDL-TG are “okay” and apoB is “terrible”.

Again: if you can easily get apoB, do get it. If not, LDL-C, non-HDL-C, and eLDL-TG will do the job.

A_User

#1456

I meant compared to apoB.

If your LDL-C, non-HDL-c, and eLDL-TG are all in the 5th percentile, then that’s perfectly good. Using solely anything that is based on association, with confounding with obesity or insulin resistance is a bad idea, is my point. Why it can’t replace apoB.

1 Like

adssx

#1457

5 Likes

As a layman, I really don’t understand this paper.

“The left tails of the curves are distorted by statin-treated patients (A,B), in which you see a high cumulative incidence of atherosclerosis despite very low levels of ApoB (panel A) and LDL-C”

“On the other hand, a clear, near-exponential relationship is seen for the incidence of atherosclerosis as a function of serum LDL-TG levels, with no apparent effect of statin therapy (C,F). ApoB, apolipoprotein B; LDL, low density lipoprotein.”

Is this another indicator that statins are probably worthless?

Also, I don’t understand the relationship of LDL-TG

What is the number we want to achieve?

Often, the LDL-TG will be a negative number.

On the other hand, a person with a low TG number would have a positive number.

Your help in understanding this paper would be appreciated

3 Likes